Lion Kimbro wrote a book called How to Make a Complete Map of Every Thought you Think (2003), and he published it online under a Creative Commons license because he's nice like that. His book describes a notebook system, and the results of his own experiments with that system.

One thing I noticed about the book is that it captures a lot of reusable ideas independent of the notebook system. Sometimes these are just little things, like "treatises on Ted Nelson's madness" being the only good available work on making notebooks. Perhaps he searched for notebooks too much instead of thought mapping.

People who think about organisation a lot seem to use it as a crutch instead of getting things done. Getting Things Done, the organisational system, is a lot like that. Pat Hall came up with a more useful alternative: Five Things Done, Bitch.

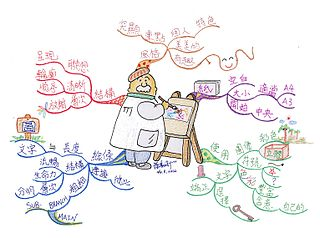

The Introduction to Complete Map made me think about how Lion's system interacts with recent cognitive science findings, and with enclimes. When you make a physical notebook, you're kind of trying to nail jelly to a ceiling. Thoughts rush about, swirling and shifting in shape and tone, hiding out of view and then jumping at you when you least expect them. A notebook doesn't do that. A notebook is static, even if it may be messy.

Web pages are a little better and a little worse. You can link them together, which takes out some of the mechanical drawback of pages. But you can't easily sketch in them, or make really fun layouts. They're quite constraining. Web pages are really not much better than word processors from the 1980s, at least for taking notes.

Having said that, most of your thinking doesn't take place on the level of a webpage and its layout. That simply helps to condition what you say. It helps you to structure your thoughts in a particular style. Writing for people on the web, knowing that people will probably read what you wrote, may fashion your notes just as radically as using HTML instead of jotting thoughts in ink on paper.

So a lot of the actual structure of your thoughts is at the word level. It's how you write, what you write, that is important. Taking notes is nothing to do with pens and paper, really. It's about thinking. And thinking is a very complex activity, which goes far beyond language. Language has an uneasy relationship with thinking. Usually thinking leads language, but language can also lead thinking to some extent, as in the weak Saphir-Whorf hypothesis. Toki Pona was devised to test what happens if you try to clear your language up; the same effect could probably be achieved by attempting to become a really good poet.

By taking notes, we really mean: making some impression of our thoughts. The impression won't be the actual thought, but will be more like a footprint in the mud.

Lion talks about subjects. Subjects are classes, categories, taxonomies. They can have sharp edges, like in classical philosophy, or they can be blurry and radial, as in prototype theory. A subject actually says a lot about the author. When Coleridge learned German, he made a kind of thesaurus for himself, grouping his words into different subject areas. His subjects are unique: there is no other thesaurus organised like that, no other work. It helps to show what Coleridge was thinking about the world.

Subjects can also be restrictive. Once you categorise a thing, even tentatively, you tend to constrain it. Lion noticed that taking notes on everything that he thought discouraged him strongly from actually thinking up anything new. What are the alternatives to subjects and taking notes in a restrictive way?

Note that we're not talking about anything objective. As Lion puts it, "The subjects are not logically arranged, by some sort of cosmic organization. They are arranged subjectively, by their own connections in our lives. The process of keeping these notebooks exposes the connections in your mind."

From General Principles:

The date goes in the top right corner. It reads something like ``(Sunday) 25 May 2003.'' I use the Japanese characters for Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. I highly recommend learning those particular characters.

This inspired Shorthand Day Symbols.

His colours are interesting:

Compare Bootstrap and the colour of its alert boxes. You could use those in a wiki for inline notes, with a standard template linking to an explanation or something.

From Intra-Subject Architecture:

"X - experimental, temporary (UNLINKABLE)"

Reminded me how magic links are. You can use this name:

http://glob.inamidst.com/thought-maps

anywhere in the world and get here. We might forget that we have a system of names that is unambiguous across the entire world, linking to entries in a global database. We forget how to characterise it.

Lion's idea of speeds and how they integrate into his larger system is an interesting one, and something that is difficult to address on a largely topic-based document mode site. One way to deal with it is to simply create as many pages as possible, almost like a contest to see how many pages you can create, and then to add information anywhere you like, whenever you come up with something. Create and refactor, and iterate. Getting a good balance is just part of being a good online editor.